Views: 222 Author: Amanda Publish Time: 2026-01-30 Origin: Site

Content Menu

● What Is Fused Deposition Modeling Rapid Prototyping?

● How FDM Rapid Prototyping Works

>> Step 1 – 3D CAD Modeling and File Preparation

>> Step 2 – Slicing and Toolpath Generation

>> Step 3 – Material Melting and Deposition

>> Step 4 – Support Structures and Overhangs

>> Step 5 – Cooling, Removal, and Post‑Processing

● Materials Used in FDM Rapid Prototyping

>> Common Thermoplastics for FDM

>> Engineering‑Grade and Composite Filaments

● Advantages of FDM Rapid Prototyping

>> Cost‑Effective Low‑Volume Production

>> Design Freedom and Complex Geometries

>> Functional Testing and Validation

● Limitations and Considerations in FDM Rapid Prototyping

>> Surface Finish and Layer Lines

>> Dimensional Accuracy and Shrinkage

● Applications of FDM in Rapid Prototyping and Production

>> Concept Models and Design Verification

>> Functional Prototypes and Engineering Tests

>> Jigs, Fixtures, and Small‑Batch Parts

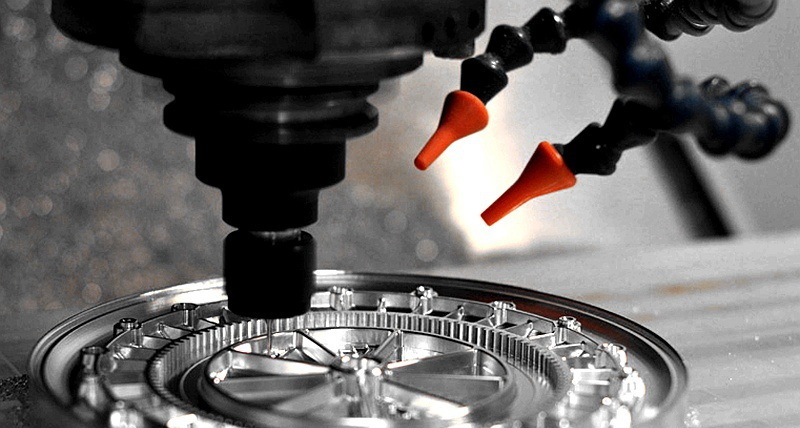

● Combining FDM Rapid Prototyping with Other Manufacturing Processes

>> Hybrid Prototypes and Functional Assemblies

>> From Rapid Prototyping to Tooling and Production

● FAQ About Fused Deposition Modeling Rapid Prototyping

>> 1. What is FDM rapid prototyping used for?

>> 2. How accurate is FDM rapid prototyping?

>> 3. Which materials are best for FDM rapid prototyping?

>> 4. Is FDM rapid prototyping suitable for production parts?

>> 5. How does FDM compare with other rapid prototyping technologies?

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) rapid prototyping is an additive manufacturing process that builds parts layer by layer from thermoplastic filaments to transform digital CAD models into physical prototypes. It is one of the most widely used rapid prototyping technologies because it is cost‑effective, easy to operate, and suitable for functional testing in many industries.

Fused Deposition Modeling rapid prototyping is a 3D printing process in which a heated nozzle extrudes molten thermoplastic material along predefined paths to form a part layer by layer. In rapid prototyping projects, FDM converts 3D CAD data into accurate physical models that can be used for design verification, assembly testing, and low‑volume functional parts. Because the process is additive, complex geometries, internal channels, and lightweight structures can be produced with minimal tooling and short lead times. Within modern product development cycles, FDM rapid prototyping has become a standard method for quickly turning ideas into tangible engineering samples that can be inspected, tested, and improved.

For manufacturers, FDM rapid prototyping offers a practical pathway to evaluate different designs, simulate performance, and communicate with stakeholders without investing in expensive tools in the early stages. Engineers can produce multiple variants of a design, adjust key dimensions, and verify fit with mating parts in just a few days. As a result, FDM rapid prototyping helps companies react to market feedback and engineering changes far more efficiently than traditional methods. When integrated into a complete manufacturing workflow, it also serves as a bridge to CNC machining, sheet metal fabrication, molding, and mass production.

FDM rapid prototyping follows a digital‑to‑physical workflow that allows engineers and designers to move quickly from concept to part. Understanding this workflow helps optimize design files and select the right parameters for each prototype.

The process starts with a 3D CAD model created in professional software such as SolidWorks, CATIA, Creo, or similar engineering tools. The 3D model is then exported into a neutral file format, most commonly STL or 3MF, which approximates the solid geometry using a mesh of triangles. Before rapid prototyping begins, this STL file is imported into slicing software, where the operator sets parameters such as layer thickness, infill percentage, build orientation, and support structures.

During this stage, design for additive manufacturing considerations are applied to improve printability and performance. Fillets can be added to reduce stress concentrations, wall thicknesses adjusted to avoid warping, and embossing or debossing adjusted to remain legible after FDM rapid prototyping. By preparing the CAD model with FDM constraints in mind, designers reduce failures, improve consistency, and shorten the iterative rapid prototyping loop.

Slicing software converts the 3D model into hundreds or thousands of 2D layers depending on the specified layer height. For each layer, the software calculates toolpaths that define how the nozzle will move in the X–Y plane and when the build platform should step down along the Z axis. In rapid prototyping, slicing parameters directly influence surface quality, dimensional accuracy, strength, and build time, so different settings are often tested to find the best balance for each project. The final slicing result is a machine‑readable file that includes temperature settings, movement commands, and extrusion amounts.

For example, a designer may generate two slicing profiles for the same rapid prototyping job: one with very fine layers and dense infill for a functional test, and another with thicker layers and lower infill to quickly validate appearance and ergonomics. Both prints come from the same CAD model, but each serves a different purpose in the rapid prototyping phase. This flexibility is one of the reasons FDM remains popular across industries at different stages of development.

During FDM rapid prototyping, thermoplastic filament is unwound from a spool and fed into a heated print head. The filament is melted to a semi‑liquid state and extruded through a fine nozzle, usually between 0.2 and 0.6 mm in diameter. The nozzle traces the toolpaths defined by the slicing software, depositing thin beads of material that immediately solidify and bond to the previous layer. As soon as one layer is complete, the build platform moves down slightly, and the next layer is deposited until the entire prototype is built.

The stability of this deposition process is crucial for successful rapid prototyping. Consistent filament diameter, stable extrusion temperature, and accurate movement of the motion system all contribute to dimensional quality and surface finish. By tuning these variables, experienced operators can push the limits of FDM rapid prototyping and achieve reliable results even on complex geometries and high‑performance materials.

Many rapid prototyping designs include overhangs, bridges, internal voids, or complex free‑form surfaces that cannot be printed in mid‑air. In FDM rapid prototyping, this problem is solved by generating support structures from the same or a different sacrificial material. Dual‑extruder printers can use one nozzle for the main build material and the other for soluble support material that is later removed chemically. Proper support design is critical to achieving accurate dimensions while minimizing post‑processing time and material waste.

Good design practices can reduce the need for supports and improve overall productivity in rapid prototyping. For example, designers may add self‑supporting angles, split parts into multiple components that are assembled later, or reorient the model to reduce overhangs. When these strategies are combined with intelligent support generation, FDM rapid prototyping delivers high‑quality parts with shorter lead times and lower material consumption.

Once the build is finished, the part is allowed to cool before being separated from the build platform. Supports are then mechanically broken away or dissolved in a suitable solution, depending on the materials used. In rapid prototyping workflows, post‑processing often includes light sanding, bead blasting, or applying coatings to improve surface finish and simulate production‑grade appearances. For functional prototypes, threaded inserts, metal components, seals, or electronic modules can be added after FDM printing to create fully assembled mechatronic prototypes.

Post‑processing is also the moment when rapid prototyping transitions toward customer‑facing samples. Parts can be painted to match brand colors, textured to resemble injection‑molded surfaces, or labeled to show engineering revisions and dates. These additional steps allow FDM rapid prototyping to support not only engineering tests but also marketing reviews, trade show samples, and investor presentations.

Material selection is a key factor in FDM rapid prototyping because it determines mechanical performance, heat resistance, and application suitability. Choosing the right filament ensures each prototype reflects the conditions of real‑world use as closely as possible.

Several thermoplastics are commonly used in FDM rapid prototyping:

- PLA (Polylactic Acid): Easy to print, good dimensional stability, and suitable for visual rapid prototyping models that do not require high heat resistance.

- ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene): Tough and impact‑resistant, widely used for functional rapid prototyping parts and engineering components.

- PETG (Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol): Good chemical resistance and toughness, suitable for functional rapid prototyping where moderate mechanical strength is needed.

- Nylon (Polyamide): High strength and good wear resistance, useful for rapid prototyping of parts that experience friction or repeated loading.

- TPU and other elastomers: Flexible materials that allow rapid prototyping of gaskets, seals, soft touch parts, and wearable components.

These materials cover a wide range of properties, allowing rapid prototyping teams to simulate everything from rigid housings to flexible joints. By testing prototypes in the correct material class, engineers gain confidence that the final production parts will perform as intended.

For more demanding rapid prototyping applications, engineering‑grade thermoplastics are used. Examples include PC (polycarbonate), PEEK, PEI, and high‑temperature nylons, which can withstand more extreme environments such as elevated temperatures, aggressive chemicals, or repeated mechanical stress. Composite filaments that incorporate carbon fiber, glass fiber, or other fillers increase stiffness and reduce weight, making them ideal for lightweight jigs, fixtures, and structural prototypes. When combined with FDM rapid prototyping, these materials enable production‑like performance, giving engineers realistic data early in the development cycle.

These high‑performance materials push FDM rapid prototyping beyond simple mock‑ups into the territory of serious engineering tools. End‑use parts, customized tooling, and low‑volume functional components can all be produced using the same equipment that once handled only visual models. This evolution is a key reason FDM rapid prototyping has been adopted by automotive, aerospace, robotics, and medical device manufacturers worldwide.

FDM rapid prototyping is popular because it delivers several practical advantages in product development and small‑batch production.

Rapid prototyping with FDM allows companies to significantly shorten development cycles by producing models within hours or a few days instead of waiting weeks for traditional tooling. Design teams can quickly evaluate multiple iterations, adjust dimensions, change ergonomics, and validate mechanical concepts. This iterative rapid prototyping loop reduces the risk of costly design errors and helps launch products to market faster.

The faster feedback provided by FDM rapid prototyping also improves collaboration between departments and external partners. Industrial designers, mechanical engineers, manufacturing engineers, and marketing specialists can all evaluate the same physical prototype and provide input early in the process. This shared understanding reduces miscommunication, supports better decisions, and enhances the overall quality of the final product.

Because FDM rapid prototyping does not require dedicated molds, dies, or complex fixtures, the upfront cost is low compared with injection molding or casting. For small batch production, pilot runs, or custom components, FDM rapid prototyping provides an economical alternative that still delivers functional parts. This makes it especially attractive for startups, research organizations, and OEMs that need to test multiple configurations without committing to expensive tooling.

In many cases, the same setup used for rapid prototyping can be leveraged for bridge production and spare parts. When demand is uncertain or volumes are limited, FDM rapid prototyping can supply high‑value parts without the financial risk of building hard tooling. This flexibility is particularly valuable in niche markets, aftermarket support, and customized system integration.

Additive manufacturing enables designs that are impractical or impossible using subtractive methods. With FDM rapid prototyping, internal lattice structures, organic shapes, conformal channels, and lightweight frameworks can be created as a single build. This design freedom encourages engineers to explore innovative solutions and optimize parts for weight, strength, or fluid flow without being restricted by traditional manufacturing constraints.

For example, heat exchangers, drone frames, ergonomic grips, and complex ducting components can be redesigned for FDM rapid prototyping to reduce weight and material use while maintaining performance. These optimized geometries can then inspire new approaches when the product transitions to metal fabrication or injection molding. In this way, rapid prototyping becomes a powerful driver of innovation rather than just a verification step.

Unlike purely visual models, FDM rapid prototyping can produce parts that endure real‑world testing. Depending on the chosen material and infill, prototypes can be used for snap‑fit assemblies, fatigue testing, thermal evaluations, or even short‑term end‑use applications. This capability is valuable in sectors such as automotive, consumer electronics, industrial equipment, and medical devices, where realistic testing during rapid prototyping reduces the number of physical trials required later in the development process.

By performing mechanical, environmental, and assembly tests on FDM rapid prototyping parts, teams can refine designs and identify potential failure modes before investing in molds and tooling. This front‑loaded learning improves product reliability and reduces warranty risks after launch.

Despite its strengths, FDM rapid prototyping also has limitations that must be managed through proper design and process control.

Because FDM builds parts layer by layer, visible layer lines are almost always present, especially on curved surfaces. For high‑end aesthetic models, this typical surface texture may require secondary operations such as filling, sanding, and painting. During rapid prototyping, designers must decide early whether visual perfection is essential or whether a functional but slightly rougher surface is acceptable for the current project stage.

In many cases, using FDM rapid prototyping for internal engineering reviews and switching to finer‑resolution technologies (such as stereolithography) for final cosmetic samples is an efficient strategy. This combination allows teams to control costs while still achieving the surface quality needed for customer presentations and marketing materials.

Thermoplastics expand and contract under temperature changes, which can introduce dimensional variation and warping. In FDM rapid prototyping, this is more pronounced with materials like ABS that require higher extrusion temperatures. Proper printer calibration, controlled chamber temperature, and optimized part orientation are essential to minimize distortion, especially for large flat components or precision assemblies. For critical dimensions, FDM parts are often measured and compensated in subsequent design iterations.

To get the best results from FDM rapid prototyping, engineers also use design rules such as minimum wall thicknesses, corner radii, and hole diameters that reflect the behavior of the chosen material. These rules ensure parts print consistently and can be inspected against specification with confidence.

FDM rapid prototyping generates parts with inherent anisotropy, meaning mechanical properties differ between directions. The interlayer bonding in the Z direction is typically weaker than the strength in the X–Y plane, so tensile and impact performance depend on part orientation. Engineers must consider loading directions when designing rapid prototyping components and choose orientations that align the strongest axes with the primary stress paths. In some cases, design modifications or thicker sections are used to compensate for anisotropy.

Understanding this anisotropy is essential when moving from rapid prototyping to low‑volume production using the same FDM process. By orienting parts consistently and designing around directional properties, manufacturers can deliver repeatable performance and reduce the risk of unexpected failures in service.

FDM rapid prototyping is now used across many industries, from conceptual modeling to end‑use part production.

In the early stages of rapid prototyping, FDM is ideal for building concept models that communicate design intent. Designers and stakeholders can physically handle the model, evaluate proportions, and verify ergonomics. These tangible prototypes help identify design flaws that may not be visible on a computer screen and support more efficient communication across design, marketing, and management teams.

Concept models produced through FDM rapid prototyping are also valuable for customer interviews and user testing. By observing how users interact with early prototypes, companies can refine form factors, control locations, and user interfaces long before final tooling is built.

For engineering teams, FDM rapid prototyping provides functional prototypes that can be used in stress tests, fit‑and‑assembly checks, and subsystem integration trials. For example, enclosures for electronic units can be rapidly prototyped to test PCB fit, connector clearances, airflow paths, and cable routing. Mechanical components such as brackets, housings, and fixtures can be printed to verify load paths and potential interference before committing to high‑volume manufacturing methods.

This level of functional testing during rapid prototyping builds confidence in the design and dramatically reduces the likelihood of expensive changes during pilot production. It also makes it easier to prove concepts to customers and investors when launching new products or custom solutions.

Beyond traditional rapid prototyping, FDM is frequently used to create custom tooling, assembly jigs, and quality fixtures that support production lines. In low‑volume manufacturing or specialized equipment, FDM rapid prototyping can effectively bridge the gap between prototyping and production by supplying replacement parts, test fixtures, and customized accessories. This flexibility reduces downtime and enables highly tailored solutions in industrial environments.

As more companies adopt digital inventories and on‑demand manufacturing, FDM rapid prototyping becomes a strategic capability. Instead of storing large quantities of spare parts, manufacturers can store 3D models and produce parts when needed, reducing inventory costs and ensuring quick response to field failures.

Integrated manufacturing providers often combine FDM rapid prototyping with CNC machining, sheet metal fabrication, and molding to deliver complete solutions from concept to production.

By integrating FDM rapid prototyping with precision CNC machining or metal fabrication, it is possible to create hybrid prototypes that closely match final production assemblies. For instance, an FDM‑printed housing can be combined with CNC‑machined metal inserts or sheet metal brackets to simulate the full mechanical behavior of the final product. This hybrid rapid prototyping approach is particularly useful when testing thermal paths, structural stiffness, sealing performance, or mounting interfaces that will eventually be produced in metal.

These hybrid assemblies allow teams to verify manufacturing feasibility, assembly sequences, and serviceability. They also help OEM customers visualize the final product and evaluate how plastic, metal, and electronic components interact before committing to large tooling investments.

Data and feedback from FDM rapid prototyping are used to refine designs before cutting molds or setting up mass production lines. Once the design is frozen, CNC machining and mold manufacturing can proceed with greater confidence, reducing the risk of expensive rework. In some cases, FDM rapid prototyping is also used to create sacrificial patterns for casting processes or to validate mold designs prior to production. This integrated workflow provides OEM customers with a smooth transition from prototype to mass production.

In a typical project, early FDM rapid prototyping models validate general architecture, later hybrid prototypes confirm critical interfaces, and finally precision machining and molding ensure production quality. By managing these stages carefully, manufacturers deliver robust products while controlling cost and lead time.

Fused Deposition Modeling rapid prototyping is a versatile, cost‑effective, and widely accessible additive manufacturing technology that transforms digital models into physical parts layer by layer. It supports fast iterations, functional testing, and complex geometries that are difficult or impossible with traditional subtractive processes. When combined with other capabilities such as CNC machining, sheet metal fabrication, and tooling, FDM rapid prototyping becomes a powerful pillar in a complete product development and manufacturing ecosystem. For OEM brands, wholesalers, and manufacturers, adopting FDM rapid prototyping significantly shortens development cycles, reduces risk, and accelerates time‑to‑market, while also enabling innovative designs and customized solutions that differentiate products in competitive markets.

Conntact us to get more information!

FDM rapid prototyping is used to create concept models, functional prototypes, jigs, fixtures, and small‑batch production parts. It allows engineers and designers to physically evaluate form, fit, and function before committing to tooling. By supporting frequent design iterations, FDM rapid prototyping reduces development costs, improves communication across teams, and shortens time‑to‑market.

The accuracy of FDM rapid prototyping depends on printer calibration, material, and process parameters, but typical tolerances are suitable for most engineering prototypes and assembly tests. For high‑precision features, parts can be post‑processed or combined with CNC‑machined components. By applying design rules and performing several rapid prototyping iterations, teams can achieve the dimensional control required for demanding applications.

The best material for FDM rapid prototyping depends on the application's mechanical, thermal, and chemical requirements. PLA is ideal for visual models, ABS and PETG work well for general‑purpose functional prototypes, while nylon and composite filaments are suited for higher loads and wear. Engineering‑grade materials such as PC, PEEK, and high‑temperature nylons are chosen when prototypes must withstand demanding conditions, so selecting the right filament is a key part of planning any rapid prototyping job.

FDM rapid prototyping is increasingly used for low‑volume production, custom components, and specialized tooling where traditional processes are too expensive or slow. For large quantities and simple geometries, injection molding may still be more economical. However, for customized designs, replacement parts, bridge production, and continuous product improvements, FDM rapid prototyping offers real advantages and can serve as a practical complementary process to conventional manufacturing.

Compared with other rapid prototyping methods such as SLA, SLS, or metal additive manufacturing, FDM rapid prototyping is generally more affordable and easier to operate. It offers a broad selection of thermoplastic materials and is well suited to functional prototypes and tooling. Other technologies may provide smoother surfaces, higher resolution, or metal parts, but FDM rapid prototyping remains one of the most practical and versatile choices for everyday engineering, product development, and small‑batch production tasks.

1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/fused-deposition-modeling

2. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/RPJ-04-2019-0106/full/html

3. https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/lpts-2013-0028

4. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jmce/papers/ICAET-2014/me/volume-1/14.pdf

5. https://www.daaam.info/Downloads/Pdfs/proceedings/proceedings_2012/014.pdf

content is empty!

Top CNC Machining Parts Manufacturers and Suppliers in Japan

Top CNC Machining Parts Manufacturers and Suppliers in Germany

Top CNC Machining Parts Manufacturers and Suppliers in Italy

Top CNC Machining Parts Manufacturers and Suppliers in Russia

Top CNC Machining Parts Manufacturers and Suppliers in Portugal